Post-processing.

Talking with Bill and Kailan about addiction, caring for self and others, and what it feels like to be documented.

From September 2024 to February 2025, I spent about six months working with New York Times reporter Jan Hoffman about the surge of meth use in Maine. Since it was published in April, it’s become one of the projects I get asked about the most. The topic is a bit of an outlier for me, I typically work on softer stories about people and nature, art, travel, and the like. But editor Matt McCann trusted me with this story, and gave me the time and parameters I needed.

Sometimes when I receive an assignment, my editor will send me a complete draft to work with. In other cases, like this one, the reporter is researching and building their story at the same time I am photographing it. Jan spent a lot of time on her own conducting interviews, doing research, and building on her extensive experience as a health reporter who has covered addiction for many years. We spent a lot of time together getting to know people in Portland, Maine’s East Bayside neighborhood. This included helpers, like Bill Burns, and people, like Kailan, who use methamphetamine and other substances.

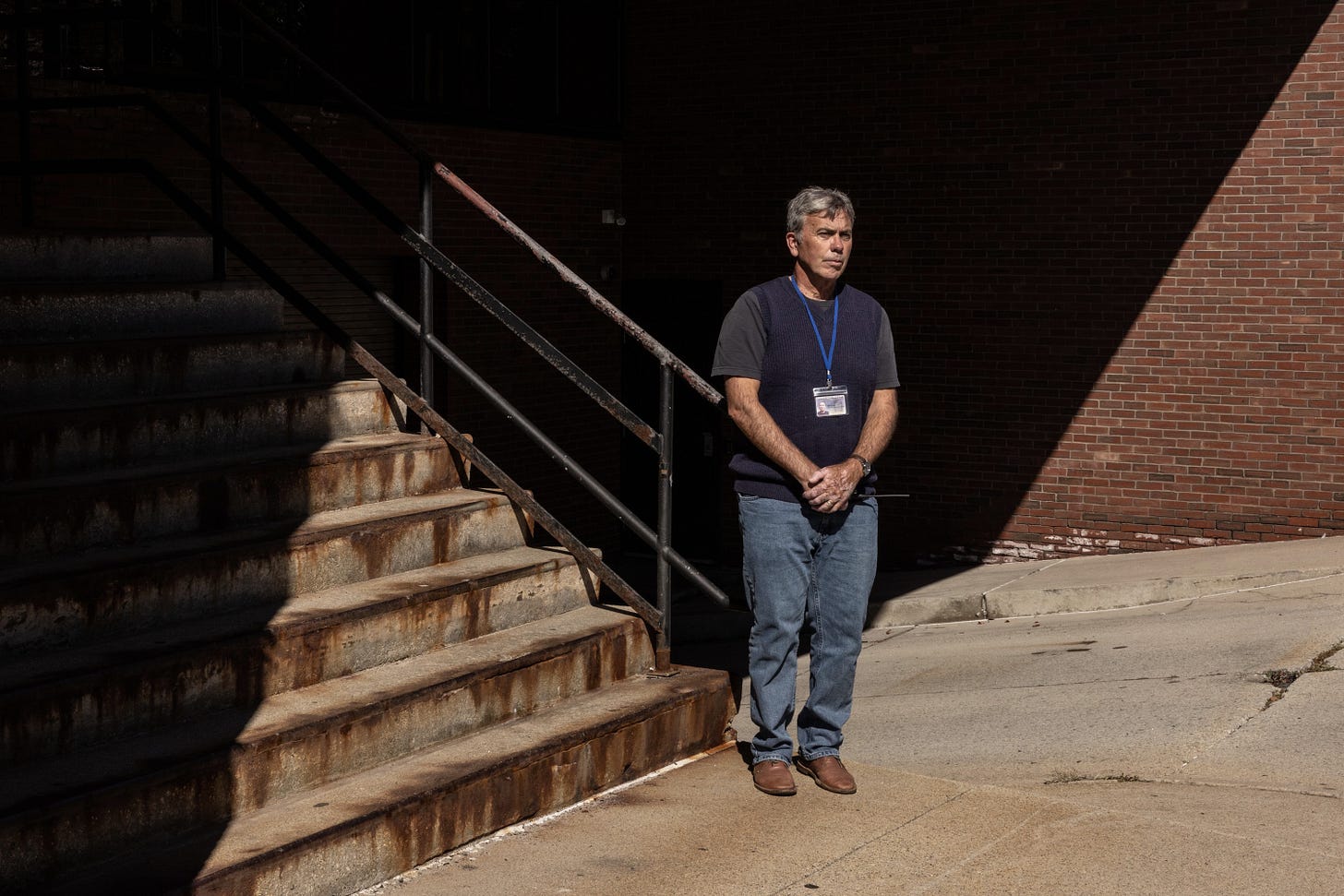

I spent a lot of time with Bill as he responded to acute needs in the community or in the car while he drove people to the methadone clinic. His work exists in a bit of a gray area: he used to run the local shelter, but swears he isn’t a social worker. He works for the police department but makes no arrests. He thinks deeply and cares a lot: he knows statistics in the same way he understands poetry.

I met Kailan on Halloween, she arrived to the methadone transport in a plush, furry jacket. She reminded me of Margot Tenenbaum. I took her photo in the sunshine with her sunglasses and fabulous outfit. Later, I photographed her smoking meth, crouched in the snow under the protection of her winter coat.

Projects like this really stay with you. I had more follow up questions and people had asked me questions that I couldn’t answer. So, I decided to head back to Bayside. I brought some prints for people involved in the project and both Bill and Kailan gave me their time to talk about the article including what it felt like to participate in it.

BILL BURNS

What it like to be a part of this article? Us showing up and you showing us your world?

It felt like… what’s the novel with Virgil as the guide into the inner spirals into hell? Dante’s Inferno. I was the guide. That’s where we are all day, every day. And so it was like, “Okay here we go.” How can I help to communicate something important and significant about what is happening here? The way you and Jan treated the folks that we were talking to gave me no pause whatsoever. Some stories are not as evocative or representative of the real experience of people. We were really lucky to be getting people to talk as they did and to allow their pictures to be taken and their quotations to be included.

I thought going into this story that it might be hard to find people to tell us about their meth use. But I was surprised that people were very open with us from the beginning. I was often surprised by what I saw, like the day I went on the methadone clinic transport and there had been a death in the community the day before. Each time someone get in the car, they would be informed about the tragic death and a natural rhythm happened. They would cry, people would talk about him and share memories. They’d also make a plan to check in with other people or get additional care to help with sobriety plans now that there was this added element of grief. It was a level of care I didn’t expect.

The first time you or I were to experience something like that, they’d send us to grief counselors or something. Years ago, all your friends would come over. They’d bring you a covered dish or something. And all those street friends just did that for the person in need that day. They just knew. What grief counseling?

You don’t outsource that care.

Exactly.

I’d like to ask you one of the big questions I’ve been asked repeatedly about this story. I was so focused on gaining consent throughout this project, and recalibrating that consent as someone was using meth because I knew their headspace would change. I was so focused that I didn’t think about any legal ramifications about someone being pictured doing something illegal. Was I putting people in danger by making and publishing those photos?

From what I know, there’s nothing they could be charged with. If you are smoking meth and someone took a picture, no one is going to prove that. Nothing is going to happen with that. I have to say, I don’t turn away when someone is using in front of me. With folks with addiction issues, we don’t tend to turn away. People are often using spice [a synthetic cannabinoid], which has this legal gray area. But a lot of my role is telling people this isn’t the time or the place to, say, be shooting up or hitting a crack pipe.

You say you aren’t a social worker. You work for the police department, but you also let people know that you will not be arresting them. You provide transport and get people to the care you need. So the question is, what is Bill? I came to think of you as Bayside’s dad.

I’ve always seen you as a father to the community. Both Keke and Joann have accused you of thinking they are like your children, and I’ve always said- is that such a bad thing? Someone cares about you? - Jennifer, Bill’s colleague.

If you know one addict, you know one addict right? Knowing what will work with everyone struggling with addiction is impossible - as Seamus Heaney once wrote “no song or play or poem can right a wrong inflicted and endured”. What is possible is endeavoring to see and understand the complexity before you and find a way to what’s possible. Before humans invented alphabets, Loren Eiseley reminds us we read the stars, the seasons, we guided our lives with rhythms that bound us to the natural world. Today, those markings are harder to find and for someone in the throes of a vicious, life-grabbing addiction, it is essentially impossible, the codes so inscrutable and unfamiliar that even trying to untangle them becomes a Herculean task, or is it Sisyphean?

And yet, during WWII Navajo soldiers, speakers of an inscrutable language themselves, broke codes that helped us defeat the Nazis. Our work is about breaking codes and nudging, always nudging people towards a healthier life of purpose.

I think if I was in this job for a long time, I would harden, I wouldn’t always have the discernment about when to be soft and when to be stern. I think it’s a discernment about what situation needs what approach. Sometimes people need love and sometimes they may need discipline. Maybe it’s both.

It’s an odd position because I’m not anybody’s caseworker, I’m not anybody’s therapist. I don’t have those roles. I don’t want those roles. We are trying to get people from point A to point B. Everything that I am doing is about nudging people in a healthier direction. Sometimes that looks like RKTs* (*Rice Krispie Treats, which Bill makes at home and brings on Thursdays on the methadone transport), sometimes that looks like a burger, sometimes that looks like kicking someone out of the car because she’s threatening someone else. People need love and limits. It’s a question of trying to hit the right buttons. There’s no formula, it’s all alchemy. A lot of it is just throwing stuff on the wall and seeing what sticks and creating different community. So much of it is palliative. And there’s great beauty in palliative care. It does mean not having the fantasy of “curing.”

Even after years of this of this work you still have belief and hope when people say, “I want to make a change” or “I want to get clean.”

Yeah. It’s an external expression of an internal ambivalence. I think everybody’s kind of ambivalent. You’ve seen it, they’re in the world. And in that world, like there’s gallows humor and there’s a bravado. They’re telling us very similar stories about how much dope they did, how great oxys were. And when people get sick of the ride, they really do, you know? There’s a capacity for change.

In the timeline of working on this project, I photographed an assignment where people were eating caviar one day and the next I photographed someone smoking meth under their jacket in the middle of the winter. Sometimes I felt discombobulated. I had a little trouble synthesizing those disparate realities. But you have to do that every day. Does it ever feel surreal and strange? Or is it easy for you to compartmentalize those things?

For me, I don’t think about things in those terms. It’s not about compartmentalizing. It’s about acknowledging that life expresses itself in various ways. It’s a blessing, I have a daughter who is traveling now. A great wife, a dog, a job. I have people I really care about. I have great colleagues. And it all exists together.

KAILAN

You told me earlier that you felt like being a part of an article gave you a feeling of closure.

I have to make the right steps towards housing and getting myself more on the clean and narrow. I’m kind of tired and I’m ready to put this crap down. You can only go so far, and after a while it really starts to wear thin. And you know, while I still have an addiction, I have enough strength in me to find other resources. I have enough strength to find a psychiatrist and a doctor. And with a little limelight on my story, who knows what the scenario might be. And that’s the kind of closure I’m thinking about. I’m sensing that people care.

You left a big impact on me. One of the things I have thought about is that you and I have the same birthday. Do you remember talking about that?

When is your birthday?

Mine is November 8, 1986. When is yours?

Mine is September 29th.

I thought we had the same birthday! But are you also 1986?

Yes! But you know, [when I am using meth], it’s like you might be meeting me or my inner, or my inner’s inner.

I remember so clearly taking pictures with you in the snow. I only know what it feels like to me to be on my end, taking pictures. What did it feel like for me to be there taking photos?

You made it really comfortable. You do. You made it feel less like a job. I didn’t feel like the camera was really very much at all. No, it really didn’t. In fact, you were still there, just yourself in the moment that I think you missed a couple of opportunities.

I think you are so right, sometimes I am just listening and I forget to take pictures. What were the moments when you thought I missed?

I think when I was in the backseat of the van, telling Jan about my story.

(At this point we are both laughing.)

When the story came out, the day that the paper came out, did you get to read it?

I think it was mentioned. And no, I didn’t like run to try to find a copy. And then when somebody said, “Did you read it yet?” and I was like, “No.” But someone gave me the middle of the paper.

It’s just been such a hard day today. You know, I woke up early and couldn’t find my stuff. It was really aggravating. And my friend came over but I wanted to go to the clinic but he wanted to take me away from that. Why would a friend want to do that to me?

One of the things I think about is that we showed up and spent time with you and made an article that goes out into the world. But everything keeps happening. You still woke up today and have been having a hard day, but there’s no one there taking notes or photographs. Are there things that have happened since then that you wish I or other people knew?

God, I feel like I’ve had that thought. I’ve had a few little bright light ideas, like oh, I wish I’d told them this or added this. But I can’t think of what they were now. I wish I could add that some of our resources feel like they may be closing. Not just that, but there are things I don’t have yet that I need. It just means I need to buckle down even more so to ensure that I’m secure. Sometimes the things that need to happen the most, we end up doing the opposite because we’re just so used to living this vicious cycle type of life. You know? It’s like procrastination. You just do the opposite of what really needs to happen. It’s a lot of pressure.

Do you have a picture for what stability would look like for you?

Yeah. The other day I walked past the apartment that we had when my son was a toddler. I feel so bad I lost all that. I just think “What happened? How did I lose all that?” I sometimes feel like the whole scheme is like we were all really set up for failure almost.

Is there anything that is giving you hope or making you feel better?

You. People like Bill.

Can I ask you one more thing about when we were taking photos? It was really important to me that I asked you, as we were taking pictures, if it was okay that I take pictures. I always wanted to even know what I was doing and feel comfortable with me there. But why did you say yes? A lot of people would have said, “No, you can’t take a picture of me smoking meth.”

Oh, I expected that. I really did. I guess, like some people were shocked by it afterwards. But you guys were doing an article on that specific thing, of course you are going to be curious. So I expected it.

A lot of people told me that they thought you were really brave.

That’s what I was hearing, too. But I don’t really get that part.

I think it’s because it’s not something that a lot of people see. But it’s something you do, I’m assuming, multiple times a day. I think some may wonder how you felt comfortable sharing something that other people may be uncomfortable with.

Oh, and maybe they were wondering how I’d be so ballsy to go against the law. It’s because I know what’s really going on below the surface and how this all came about. I know what happens behind the curtains that no one can see behind. And I know I’m not the bad guy.

Thank you to Bill and Kailan for their generosity during the original reporting for the New York Times as well as for this little follow-up piece. Many people in Portland gave us their time and stories.

You can read the articles in the New York Times here and here. In June, I also worked on a story with Jan Hoffman about contingency management programs, a new program to address stimulant dependency, which you can read about here.

I think it's really amazing that you give her hope what a great compliment I think you should put that down as the biggest compliment of your life.