Going Through It.

Unsolicited Advice for the Aging Parent / Grief Eras

One thing I’m known for is really bringing the party down by shifting the conversation towards something intense. I can’t help it! It’s somehow baked into the person I am. I like breaking trail towards the stuff with substance. I feel like posting about grief in the no-mans-land days between Christmas and New Year’s is a bit of an interruption to the fun, but here goes.

When my dad died, it happened suddenly. For a while, I knew what to do because I could only do the basics. I called the people I needed to call.I booked plane tickets home. I walked around the woods and cried until I couldn’t anymore.

In the years leading up to that day and the few months since, I had to figure out some things that would help me through the Aging Parent Era and the Grief Era. I’m not a therapist and I’m new to this. But from the beginning, I’ve always wanted to be clear and open about what I was experiencing because I believe so much of it is shared in some way. And I’ve found myself recommending the same set of things.

The Aging Parent Era (or, the “Someone You Love is Facing the End” Era):

Make a playlist with your close ones, focused on their favorite songs. I made a playlist with my dad as his Alzheimer’s worsened. I prompted him to remember favorites from throughout his life. Tom’s Ultimate Playlist has Peggy Lee from his childhood, the Rolling Stones from his bad boy high school years, and Lightnin’ Hopkins from his Blues phase. I can listen to it whenever I need to feel closer to him.

I also am glad I wrote down his bread recipe and know how to make his homemade salad dressing by heart.Storyworth. Maybe you’ve seen ads for it and I’m an evangelist for it now, too. I set my dad and mom up with an account each, and it sent them weekly prompts to write about. Sometimes I chose the questions and sometimes Storyworth automatically selected great ones. They both wrote about memories, preferences, lessons learned, etc. A subscription comes with a beautiful printed book of the questions and responses when you are ready.

Palliative Care. A palliative care doctor is different than other practitioners because their sole focus is balancing a patient’s wishes for their remaining time. Quality of life is the priority. I’ve been surprised to talk to people navigating mortality who haven’t known it wasn’t a resource, and others thought it was only for the “very end.”

Typically, palliative care is suggested for any person given a terminal diagnosis. My dad’s palliative care doctor helped us as a family meet my dad’s priorities (like going on a trip or continue exercising) and also prepare for what was ahead. On the day my dad died, she helped my mom and me navigate the strange experience of a beloved’s death.Therapy. THERAPY. As soon as I realized that I would be navigating the decline and eventual loss of a parent, I started searching in earnest for a therapist that would be a good match for me. I found her. She helped and is still helping. I’m a very different person than when I started, in the best way. I often imagined that my grief was like a big balloon that would need to be released throughout my life. Better to let it squeak out slowly over time then in one painful, ruinous burst.

I started doing this meditation thing where I’d lay in my bed with my hands on my chest and hold a vision of my dad (sometimes other people) in my mind or heart. I’d let that vision of him of him move through different eras of life, sometimes based on photographs or actual memories. I’d imagine him as a little kid or rebellious teen or a guy in his 40s who liked to bike and ski. My dad was my dad for only part of his life: there was a lot of his existence that I wanted to incorporate into my grieving.

The Grief Era:

Grief reminds me of the children’s song “Going on a Bear Hunt:”

We can’t go over it

We can’t go under it

We’re just gonna have to go through it

Honestly, it’s all so individual and connected to specific circumstances of the death or life change: who was lost, how the change occurred, whether it was expected or sudden, how complex the relationship is, etc.

Consider clear, direct language about both illness and death. These topics are hard to talk about, I’m okay with any way that people can find to speak them. And sometimes we’ll mess up. For me, I prefer words like “die” and “death” over euphemisms. I like it when people use my dad’s name, Tom, in conversation. It feels good to speak of him in a real way. I am open about the way he died, telling the story about how it happened and the dual diagnoses that lead up to that day (you can read about that here).

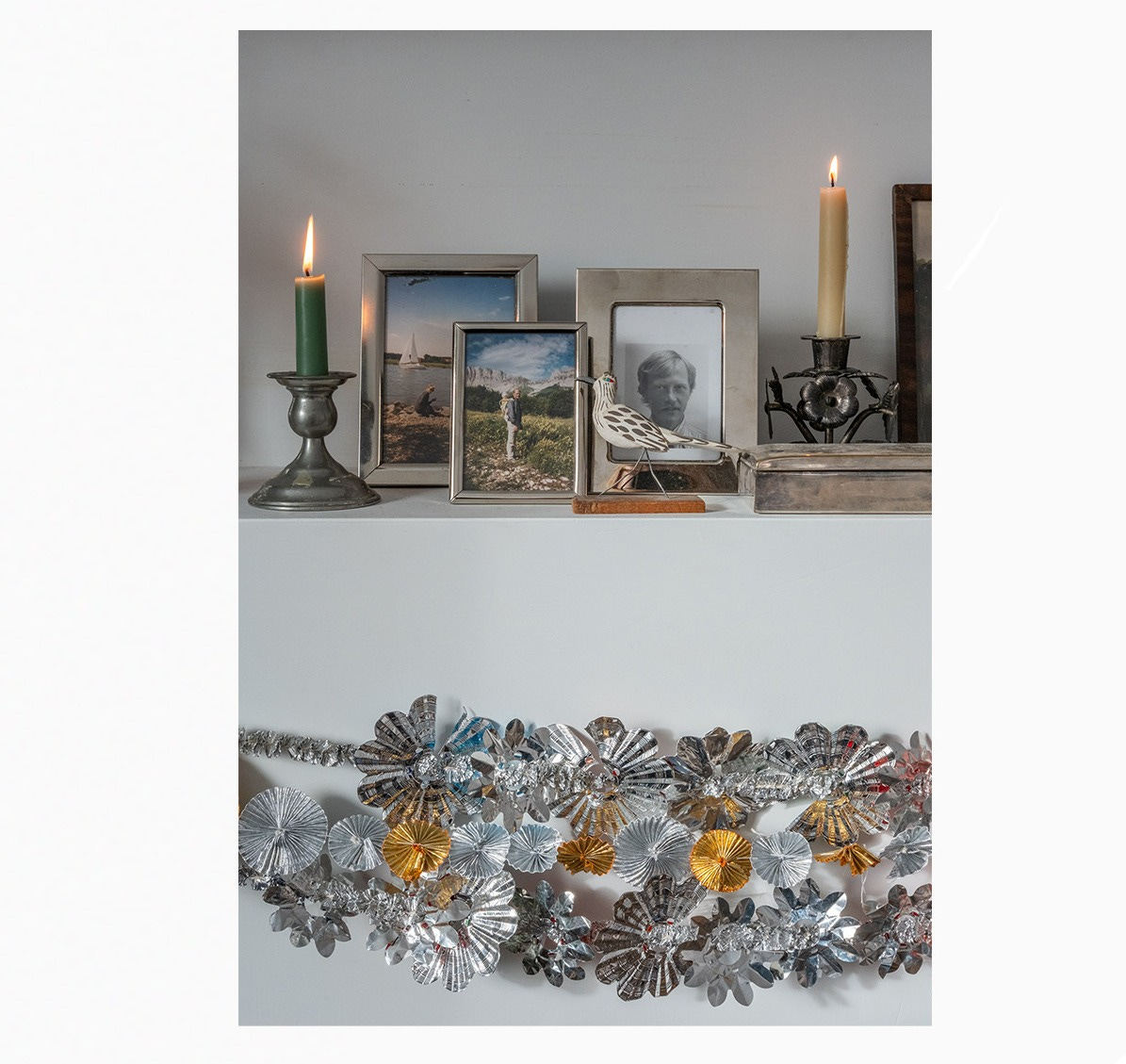

I am also a believer that, when appropriate, it can be meaningful to write about cause of death in an obituary. Because it can be taboo, we often have curiosity or avoidance around death. People sometimes avoid speaking directly because they want to prevent hard feelings. But any grieving person is already experiencing so many emotions they can not be avoided. And anyone who is not actively grieving may benefit from brief contemplation of the reality of death.Make a shrine or altar. We made a shrine for my dad both at my mom’s house and mine. It had photos of him, his wedding ring, his watch, packs of his favorite gum, the three tums he laid out by his bed every night, candles, flowers, notes from friends, an envelope with his handwriting. It was where we put things that were so personal or specific to him, they needed a place of importance. Every night we lit candles and I gave him my thoughts.

My friend texted me recently about a college friend who had died. It hit her hard, but she didn’t know what to do about the grief. They weren’t as close as they had been. Making a shrine is helpful for this strange type of grief, too- the one where you feel hit with sadness but might not be able to make the memorial, or the relationship contained distance or pain.

Before my dad’s death, when I’d experience miscellaneous or incidental grief throughout my day, I would sometimes light a candle in the evenings and think about the sadness I’d absorbed: an acquaintance’s new diagnosis, violence on the news, the friend who lost their job.A creative outlet. I started a collage journal about a month before my dad died, and suddenly after he died it felt like all I could do. One day, his best friend came to visit and it broke my heart, so I went upstairs to cut and glue through my feelings. Making things seems to help me move through the strangeness of it all. Right before his burial, I mixed essential oils with a base oil to bring to the funeral home so they could anoint his body before his burial.

Photography has been a help, too. When my grandmother was moving from her home in Ennis, Montana, I photographed her belongings. And when gathering back in Montana for her memorial, I started photographing another series that helped me understand how we would now step into her role as family historian. (I also wrote about her for “the Lives They Lived” in the NYT.)The song that gets you through. For me, it’s Change by Big Thief. Right after a turn in my dad’s prognosis, I was stuck driving through the backroads in South Africa by myself with no phone service. Just me and the road and this song over and over, sobbing. The music felt like an excavation project.

I sent it to my mom after my dad passed and a family friend sang it at his memorial. And in October, Big Thief ended their show in Maine with a big sing-a-long to Change. Good art can bring about some needed catharsis. Some people like to listen to posts or read books about grief. My go-to is music. It gets me out of my head and into my feelings.

The Grief Deck. My friend sent me this artist-made deck of prompts about grief, each card has an art work and a meditation or action that can help move someone through loss. It’s the first one I found that felt realistic and not pandering.

Rest. We have full permission to fall asleep or lounge around whenever it is safe and needed. Rest and naps are key survival components even when we aren’t grieving, but my biggest “grief symptom” has been exhaustion. I maintained a lot of my stamina throughout my dad’s illness and in the organizing phase that comes after someone’s death. But now I just want to be less capable and more able to identify when I don’t have to be so “on it” and sharp. Let me be off and soft.

I saw an interview with musician Neko Case about how she felt that forgiveness isn’t a state you achieve, but an atmospheric condition you find yourself in. I feel that way about grief, mine feels like a set of weather patterns that might not feel like another’s climate.

This experience is both individual and collective. My job is to recognize what’s mine to bear and should be shared. I also know that I will have other griefs that will knock me sideways. I may look back at this post and think how silly and naive I was about it all.

My dad always said, “Better than a sharp stick in the eye!” to which we always were like, “Literally everything is better than a sharp stick in the eye.” We don’t know about the sharp stick until it’s in our eye, and I think that’s how a lot of life and grief is. We can only do so much to prepare for it, and even with our preparations we still need to go through the storm. But I’m grateful, still, that I battened down the hatches and invited other people under my umbrella. Thank you for joining me in the rain.

This is such a fantastic list, thank you. Some friends and I began navigating deaths of family members closest to us in our early twenties and I wish we had had found writing like yours on grief. Grateful to encounter it now.

This is so lovely and different from anything I've read on the subject in the past. Thank you.